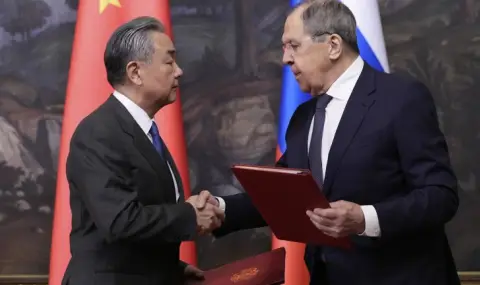

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi was probably being dishonest when he recently told Kaia Kallas, the European Union's high representative for foreign affairs and security policy, that China "cannot accept Russia losing the war against Ukraine, as that would allow the United States to focus all its attention on China", writes Alexander J. Motyl in a commentary for The Hill.

He is a professor of political science at Rutgers University in Newark and a specialist in Ukraine, Russia and the USSR.

"Focus“ provided a translation of the material without editorial intervention and with the clarification that it reflects only the author's point of view.

Why might Wang not have been completely honest? For starters, he is a diplomat, and all diplomats have a tendency to express opinions that are not entirely sincere. Confusing and keeping your opponents in the dark is a lesson that diplomats everywhere have learned.

Furthermore, Wang represents a totalitarian state with a vast propaganda apparatus that, like all such structures, tends to prefer manipulation to truth.

But the misleading nature of Wang’s private comments is most evident in the fact that, contrary to his claim that the US is China’s biggest concern right now, it is actually Russia.

Yes, China certainly wants the US out of its way, and so any distraction is a good distraction. But America is not next door and is not engaged in a drawn-out war. Despite the Trump administration’s loud statements, it has yet to resort to actual measures. Nor is it clear, as the ongoing tariff battle shows, what it would mean to take action against China.

In contrast, Russia is a much more immediate security threat, and perhaps even a threat to China.

Consider these three possible outcomes from the perspective of China’s security interests.

If Russia wins in Ukraine – whatever one defines victory – Putin will be filled with self-confidence and arrogance, having succeeded in making Russia a great power once again in his imperialist adventure. Such a Russia might be reckless enough to attack a NATO country or try to annex northern Kazakhstan, which would not be in China’s interest.

The next step would be a change in tone. A triumphant Russia could begin to flex its muscles and challenge its sworn “unrestricted” friendship with China. Perhaps the terms of the partnership could be changed to reflect Russia’s new status? Perhaps Beijing could consider paying more for energy from Russia? Perhaps China could stop publishing irredentist maps with Chinese names for Russian cities?

The eternal friendship may not disappear overnight, but it would certainly create a more complicated relationship that would test China’s patience.

If Russia loses in Ukraine – whatever the definition of loss – a whole series of highly destabilizing scenarios could arise.

A completely defeated Russia could descend into internal violence that would destabilize Eurasia. Vladimir Putin could be overthrown in a coup and his regime could collapse. Infighting among the elites would be inevitable, and civil war could break out. Non-ethnic Russians could take advantage of the chaos to declare independence, and the Russian federation could meet its ignominious end. True, China could annex large parts of the Russian Far East, but these gains would be dwarfed by the security threats that would arise from its disintegrating northern neighbor.

A war that bathes Russia in blood but does not defeat it is clearly China’s preferred choice. A weak Russia, drawn into an unwinnable war, would be punished but would still exist as a vassal of Beijing, with no alternative but to submit to its Chinese overlord. That kind of Russia suits China perfectly.

And the war need not be prolonged to achieve this goal. It could end tomorrow, because Russia is already a pale shadow of its former self. Its army is broken, its economy is on the verge of a major crisis, and its people, although largely supportive of the war, are experiencing increasing economic hardship.

It is important to note that a weakened Russia would also serve the interests of America, Europe, and Ukraine, even if such a Russia is not their first choice.

All of this suggests that Wang may have been telling the West that what China wants is what the West should want.

The implications for American policy are obvious. The United States should actively pursue what China wants: a weak Russia. This is easily achieved by helping Ukraine stop Putin, as the Trump administration may finally be doing.

Van will probably shed "crocodile tears" and pat poor Putin on the head – but he won't argue.