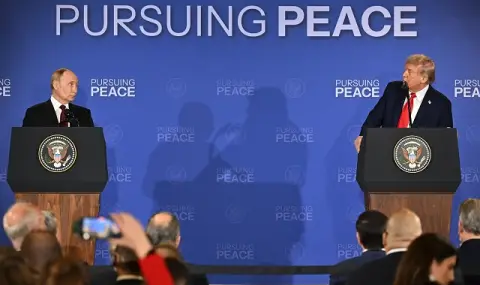

Donald Trump wants to destroy a "boundless friendship". But the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in Tianjin, followed on Wednesday, September 3, by a major military parade in Beijing, is a direct insult to the American president, just two weeks after his one-on-one meeting with Vladimir Putin in Alaska. Relations between China and Russia are currently "the most stable" among major powers, Xi Jinping assured on the eve of his next meeting with Putin. In China, the two autocrats reaffirmed how close they are in their opposition to Western "hegemony".

Historian and sinologist Philip Snow is the author of a monumental English-language study of relations between the two giants China and Russia, in which he tells of four centuries of "conflict and harmony".

In an interview with the French newspaper L'Express, he revisits the historical tensions and alliances between China and Russia and shows how the collapse of communism in Russia has paradoxically facilitated a rapprochement between Beijing and Moscow, while Mao and Stalin had long maintained terrible relations.

He also discusses possible causes of the discord, including the ever-widening economic gap and the territorial issue in the Russian Far East. But he notes that despite the long border, the two empires never fought a serious war with each other...

L'EXPRESS: The turbulent past between China and Russia is often emphasized. But in the book you point out that after the initial treaty, signed in 1689, the two countries maintained relatively peaceful relations for a long time, until the 1850s...

PHILIP SNOW: Each side emerged from the border war of the 1680s with a deep respect for the strength of the other. China's Manchu leaders realized that they were facing a huge new neighbor on their northern and western borders, and that even if they had managed to eliminate the immediate threat from Russia, it could cause problems again in a few generations. The Russians continued to yearn for their lost colonies in the Amur Valley.

In the late 1750s, they briefly considered launching a "punitive expedition" to reclaim the territory, but quickly abandoned the idea when they realized that their entire garrison in Siberia consisted of a single regiment and a detachment of horse grenadiers, and that even a planned reinforcement of 35,000 soldiers would have difficulty withstanding an expected attack by tens of thousands of Manchus and Mongols. As late as 1850, when Russia's military power was growing considerably, the veteran foreign minister, Count Nesselrode, continued to insist that the Amur region should not be occupied under any circumstances because of the "exceptional danger" posed by China.

L'EXPRESS: Did the Russian Empire subsequently act towards China like other Western colonial powers? Territorially, Russia, not the British Empire, gained most from the collapse of the Chinese Empire in the 19th century.

PHILIP SNOW: No, the Russian approach was very different. In the late 1850s, as British and French forces advanced on Peking to secure the opening of trade into the interior of China, the Russians adopted what I call a "paternalistic" policy, seeking to present themselves as friendly advisors to the Qing court and offering their services as intermediaries between the Qing and the Western powers.

They made the most of two centuries of peaceful relations with China and their relative sensitivity to Chinese etiquette: for example, the Russian diplomat, Count Putyatin, insisted on offering gifts to the Qing negotiators, while the British plenipotentiary had nothing to offer. Meanwhile, while the British were content with acquiring the Kowloon Peninsula, other Russians, on the northeastern border of the Qing empire, were quietly seizing a vast region known as "Outer Manchuria", a territory the size of France and Germany combined.

The Qing court was not blind to the ulterior motives of its Russian "uncles", but it tended to view the Russians as an evil it knew well, while the British and French, by comparison, were guests from elsewhere. The fact that the Russians managed to take control of a sparsely populated region with almost no casualties, while the British and French, in the densely populated heart of the empire, resorted to violence, also worked in their favor.

L'EXPRESS: You explain that Russia fell victim to its arrogance at the end of the 19th century, when it invaded Manchuria and even Korea. What were the consequences?

PHILIP SNOW: Until the late 1890s, the Russians maintained their paternalistic stance. In 1895, they even helped Japan withdraw from the Liaodong Peninsula in southern Manchuria, which the new imperial power had seized during the First Sino-Japanese War. But by then, Japan and the Western European powers were engaged in a fierce struggle for the territory and resources of the declining Qing Empire. The tsarist government could not remain outside this struggle, and Tsar Nicholas II was indeed known to have been driven by an "irrational desire to seize the lands of the Far East". As a result, in the winter of 1897-98, the Russian fleet invaded and occupied the Liaodong Peninsula, the region that Russia had just "liberated" from the Japanese. The Qing court was not consulted, and the tsarist government began to make all of Manchuria its sphere of influence. As a result, Tsarist Russia began to be perceived by Chinese public opinion as the most predatory of the imperial powers. Dissatisfied with Manchuria, the Russians obtained a concession from the neighboring kingdom of Korea, which gave them the right to exploit the country's forest resources.

The Japanese, already furious at their expulsion from Liaodong, saw the Russians settling in a country they had designated as the first acquisition for their planned Asian empire. In February 1904, they launched a surprise attack on Russia in Manchuria, and at the end of the war that followed the following year, the defeated Russian government was forced to cede all its possessions in southern Manchuria to Japan.

L'EXPRESS: Why was there such distrust between the two communist leaders Stalin and Mao?

PHILIP SNOW: Stalin operated on the basis of rather primitive strategic principles, summarized by the slogan "socialism in one country". From the late 1920s until 1943, his priority was to defend the Soviet Union from the Japanese threat; from 1943 onwards, from the American threat. All domestic Chinese problems were to be put on the back burner.

Despite twenty years of interaction within the Communist International, Stalin and Mao never met until the communist victory in China in 1949. Stalin is said to have told his subordinates, "What kind of man is this Mao Zedong? I know nothing about him. He has never been to the Soviet Union." Unlike almost all other leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Mao did not travel to Moscow in the 1920s to receive training in Soviet strategy and Marxist-Leninist dogma, which raised all sorts of suspicions in Stalin about his true views. He called Mao a "radish" (red on the outside but white on the inside) and a "margarine Marxist" and, judging by the NKVD files, even went so far as to denounce the CCP leader as a Trotskyist and a Japanese or American agent.

After Mao arrived in Moscow as the new leader of China in December 1949, Stalin imprisoned him for four days in a dacha in the countryside, sending his associates Molotov, Mikoyan, and Bulganin to interrogate him and determine what kind of person he was; even his feces were examined to determine his temperament!

For his part, Mao, by refusing to visit the Soviet Union, hinted as early as the 1920s of his determination to follow his own path and his vision of the Chinese Revolution as a world event, comparable in importance at least to the Russian Revolution. This was confirmed during the CCP's stay in Yan'an in the early 1940s, when his ideas were established as the party's ideology, and he himself was elevated to the unprecedented status of party chairman. Therefore, while Stalin saw Mao as a vassal, Mao saw himself as Stalin's equal and bitterly resented what he perceived as a series of Soviet reproaches.

L'EXPRESS: In your opinion, the bloody Cultural Revolution launched by Mao in 1966 was aimed not only at his domestic political opponents but also at the Soviet Union...

PHILIP SNOW: The Cultural Revolution was aimed at a wide range of different targets, from traditional culture and education to the party bureaucracy and technocratic reformers trying to return China to what Mao called the "capitalist path". And, not surprisingly, given that the Soviet Union was the main target of Mao's anger in his later years, it also affected Moscow. This is very clear when one considers the contrasting fates of the main victims of the Cultural Revolution.

Target number one, Liu Shaoqi, sometimes called "China's Khrushchev", was at the head of the traditional technocratic reformers and party bureaucrats, but he had been known for years for his closeness to Moscow and his Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy. Labeled a "renegade, traitor, and strikebreaker", he was booed and beaten by Mao's Red Guards before being placed in solitary confinement, visited only by doctors who pretended to treat him for pneumonia and diabetes while insulting him. He was eventually transferred to a hospital, where he was kept in freezing conditions, denied X-rays and medical attention, and left to die in his own excrement.

The second target, Deng Xiaoping, suffered a very different fate. He was also criticized for his technocratic activities, but was not persecuted to death like Liu; the reason given was his explicitly anti-Soviet past. Mao insisted on the need to distinguish between Liu and Deng, and the result was that Deng was simply sent to a provincial tractor repair shop before re-emerging in the 1970s as Mao's successor and China's supreme leader.

Many lesser-known figures associated with the Soviet Union were persecuted. The Soviet embassy in Beijing was besieged twice and eventually stormed: four of its diplomats were threatened and one was severely beaten, while their wives and children endured the wrath of the Red Guards before being allowed to board the plane home. The 19th-century classics of Tolstoy and Turgenev, as well as some famous Soviet novels, were declared "poisonous weeds".

L'EXPRESS: Why is it, paradoxically, easier for Russia and China to cooperate now that they no longer share a common ideology - communism?

PHILIP SNOW: Because ideology is a form of religion. Like religion, it can be a powerful bonding force in the early stages of a partnership, but it can turn against it when disagreements arise, and be used as a weapon by opposing sides. The hatred this engenders makes reaching agreements on worldly matters much more difficult. Boris Yeltsin emphasized this at a press conference during his first visit to Beijing in December 1992, when he expressed satisfaction that the "ideological barrier had been removed".

L'EXPRESS: What are the differences between the current Sino-Russian partnership and the Sino-Soviet alliance of the 1950s?

PHILIP SNOW: The most obvious is the replacement of Russia by China as the alliance's main partner. But the very nature of the partnership has changed. This is no longer a revolutionary alliance, but a deeply traditional and conservative one, inspired by the Treaty of Westphalia that ended the Thirty Years’ War in 1648—a document that Xi Jinping openly welcomed at the UN office in Geneva in 2017. The Treaty of Westphalia is based on the concept of the sanctity of nation-states and the right of their leaders to pursue whatever policies they see fit within their borders, without external interference. In the modern world, these principles are fundamentally opposed to the concept of human rights and the Western idea that governments that abuse their populations should be held accountable before an international tribunal. The same conservative attitude can be observed in cultural matters, with the Chinese and Russian governments opposing the West’s growing acceptance of, for example, gay rights.

Another obvious but little-noticed difference is the significantly longer lifespan of the new partnership. The Sino-Soviet alliance of the 1950s lasted only ten years before finally collapsing with the withdrawal of Soviet scientific and technical advisers from Khrushchev in August 1960. Since Yeltsin and Jiang Zemin announced a new "constructive partnership" in 1994, the current cooperation between China and Russia has lasted for nearly three decades and seems stronger than ever.

L'EXPRESS: In your book, you point out that China actually does not approve of Russia's territorial conquests and annexations in Georgia, which began in 2008. Why has this not threatened their alliance?

PHILIP SNOW: Russia's political and military interventions in Georgia and Ukraine contradict the Westphalian principles, to which Russia, like China, claims to adhere. Moreover, for internal reasons (Xinjiang, Tibet, etc.), the CCP leaders generally dislike secession or the breaking away of regions from existing states. But the Chinese will probably avoid raising this issue because they do not want their practical relations with Russia to be complicated again by abstract disputes. And China really needs the political support of Putin’s Russia in a world where it has few meaningful friends.

L'EXPRESS: What could call this "boundless friendship" into question in the future?

PHILIP SNOW: First, the economy. Over the past thirty years, the gap between China's and Russia's economic power has become colossal. In 2021, Western analysts estimated that China's GDP was 8 to 10 times larger than that of the Russian Federation, while Russia's GDP was surpassed only by that of Guangdong Province. Trade data confirms this contrast: China now accounts for approximately 15% of Russia's foreign trade, while Russia accounts for only 1% of China's foreign trade.

For years, China has shown a declining interest in Russian industrial products, including weapons that the Russian government has supplied to Chinese regimes for generations. At the same time, the Chinese have shown a willingness to buy huge quantities of Russian oil and gas to support the Russian economy in the face of Western sanctions imposed over Putin's war in Ukraine. In these circumstances, it is difficult to maintain the apparent equality on which the new partnership is supposed to be built.

But the Russians seem to have philosophically resigned themselves to the fact that, as one expert noted, "China has clearly outpaced Russia in every way." Rather than simply ignore the loss of potential contracts, Russian arms dealers rushed to China to sell all their equipment while they still had the chance. There were fears that Russia's oil and gas exports would turn it into China's "resource appendage", but in the context of Putin's war, the Russians had no choice but to accept the humiliating dependence that this implied.

Then there are the demographics. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, residents of the newly acquired Russian Far East were already worried about the influx of Chinese immigration into their territory. A century later, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the region no longer received enough goods from European Russia, a new panic arose over a wave of Chinese traders and workers who came to provide clothing and food for the impoverished Russian population.

Local Russians were aware that their small population of about six million in the Russian Far East faced an estimated 110 million Chinese south of the Manchurian border: it is rumored that as many as 8.5 million Chinese had already settled in Russia, and it is predicted that by 2050 the Chinese would constitute the second largest ethnic group in the country. These fears were somewhat allayed by a government census conducted in 2010, which revealed that only 29,000 Chinese in the country were registered as permanent residents; the rest are traders, farm workers, and other temporary visitors.

At least in the short term, I do not see demographics as a destabilizing factor. It is also possible that the Russian government’s current dependence on China’s tacit support means that any outbreak of Sinophobia among the population will be quickly quelled.

Finally, there is the cultural factor. During the Sino-Soviet pact of the 1950s, there was a striking contrast in interpersonal relations. Relations between the two governments were cold and increasingly tense, while at bottom the relationship between Soviet scientists and specialists and their Chinese students developed in an atmosphere of great cordiality. Half a century later, the situation is exactly the opposite.

Official relations are cordial, while relations between Russians and ordinary Chinese have deteriorated significantly. Russians no longer see the Chinese as "little brothers" whom they are obligated to help, while the Chinese as a whole no longer admire Russia and devote most of their attention to the West and Japan. Chinese and Russian leaders are aware of this and since 2006 have been trying to reconnect the two peoples with their respective cultures through a program of annual celebrations.

L'EXPRESS: Could China one day regain the territories of the Russian Far East lost in the 19th century as a result of "unequal treaties"?

PHILIP SNOW: The agreement reached in 2004 officially ended a long series of disputes between China and Russia over their border since the 20th century. However, nothing was said about Outer Manchuria, the vast 1.5 million square kilometer territory that Mao threatened to "account" for in 1964. Chinese schools teach about the Tsarist occupation of the region in the late 1850s, and in June the "New York Times" published an FSB report describing what Russian intelligence services perceive as a serious Chinese threat to the region.

It is not impossible that a future Chinese government will raise the issue at a time of deteriorating relations. This does not necessarily have to take a political form: some have suggested that global warming could one day turn northern China into a desert, leading to a mass exodus of refugees seeking food and water in the lands to the north. Recently, there have been reports of a failed Chinese project to divert fresh water supplies from Lake Baikal.

L'EXPRESS: Is the Trump administration's apparent strategy of alienating Russia from China a fallacy?

PHILIP SNOW: Yes, I think so. In recent years, Western analysts have realized that the ties between China and Russia are much stronger than previously thought. In this regard, it is worth considering several comments made on various occasions by well-informed Chinese and Russians. In 2011, a professor at the National Defense University in Beijing issued a stark warning: “As long as the pressure from the United States continues, the Sino-Russian partnership will survive.” In 2015, former Vice Foreign Minister Fu Ying wrote in Foreign Affairs that the Sino-Russian agreement was “by no means a marriage of convenience,” but rather “complex, enduring, and deeply rooted.”

And in 2018, prominent Russian scholar Alexander Lukin wrote that the foundation of this “quasi-union” was now so solid that “any dispute can be effectively resolved through the existing consultation mechanism.” Just a few weeks ago, Foreign Minister Wang Yi described the Sino-Russian partnership as the most stable serious relationship in the world today. Honestly, if you were Vladimir Putin and faced with a choice between Xi Jinping and Trump, who would you consider more trustworthy?

What is true today may not necessarily be true a generation from now, but it is important to remember the importance of restraint and caution in Sino-Russian relations, as well as the words of a Soviet diplomat who once noted that China and Russia have never fought a major war with each other.