In the 4th century, various heresies disturbed the peace of the Church. The heresy of Arius, who rejected the consubstantiality of the Son of God with God the Father, was especially widespread. Rejected and condemned by the Ecumenical Council of Nicaea (325), this heresy, however, found many followers.

The Byzantine emperor Constantius, one of the sons of Constantine the Great, was an Arian and persecuted the Orthodox bishops. In many cities there were two bishops - an Orthodox and an Arian. The people and the clergy joined one after the other, and one after the other, Orthodoxy and Arianism triumphed. But the Arians themselves were divided into two sects - pure Arians and semi-Arians, who were at war with each other. Everywhere enmity, revenge, and even bloody strife replaced the love and peace bequeathed by Jesus Christ.

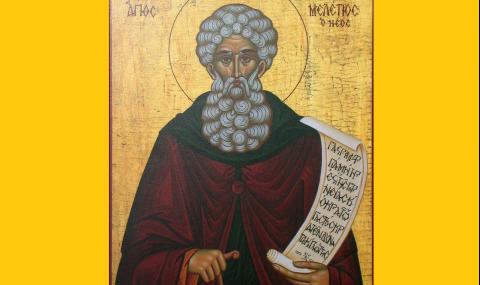

Amid these difficult circumstances, Meletius, a native of Armenia, former bishop of Sebaste, was unanimously elected archbishop of Antioch. The Arians, who outnumbered the Orthodox in Antioch, also agreed with this choice. They hoped to find a like-minded person in the new archbishop, but they soon became convinced that they had been mistaken in their expectations.

Thirty days after his election, Meletius preached in the temple. All those present – Orthodox and Arians alike – eagerly awaited his exposition of his faith. Meletius began to praise the dogmas established by the Council of Nicaea and to confess Jesus Christ as being of one essence with the Father, equal to Him in power and glory, and like Him the creator of the universe.

Here a nationwide confession of Orthodoxy greatly angered the Arians. One of the archdeacons, a supporter of the false doctrine, approached the archbishop and covered his mouth with his hand. Then the archbishop raised his hand and showed the people three fingers as a sign of the Holy Trihypostatic Trinity, and then, having folded two fingers, showed one, thereby signifying the one Godhead. The archdeacon took him by the hand, and Meletius began again with his mouth to confess and glorify the indivisible Trinity and the one Godhead, exhorting the people to firmly and unchangingly hold to the truth. The angry archdeacon now held the hand, now covered the mouth of the saint, who was so zealously preaching the true faith.

The Orthodox began to loudly express their joy and glorify the Most Holy, Consubstantial and Indivisible Trinity, and the enraged Arians expelled the archbishop from the church and from then on began to blaspheme him and call him a heretic.

With the firmness of spirit, Meletius combined extraordinary meekness and constantly tried to pacify strife and enmity. He gave his flock an example of all virtues and managed to surround himself with worthy people. He ordained St. Basil the Great, who had come from Jerusalem to Antioch, as a deacon. Foreseeing the great gifts of St. John Chrysostom, who was still very young at that time, the archbishop persuaded him to study St. Scripture, baptized him and appointed him a reader in the church.

The Arians, seeing that they had been deceived in their hopes, persuaded Emperor Constantius to depose St. Meletius and send him into exile in Armenia, and themselves elected a bishop from among the Arians. Meletius was in exile until the very death of Constantius.

After Constantius, Julian, a nephew of Constantine the Great, ascended the throne. Julian was brought up in the Christian faith, but in his soul he hated it and, as soon as he became emperor, he renounced it and began to serve the pagan gods with the greatest zeal. Having convinced himself that the cruel persecutions did not prevent Christianity from spreading, Julian resorted to more cunning measures. He declared complete religious tolerance, returned from exile all the exiled bishops - both Orthodox and Arians. He hoped that with their disputes about the faith they themselves would help him to weaken the power of Christianity.

Meletius was also returned along with other bishops. But he found the Orthodox divided among themselves: some recognized Paulinus as bishop, elected during his absence, while others awaited the return of Meletius. These disputes embittered the saint, and he meekly tried to establish peace and harmony.

Soon after this, Julian died in war. His successor, Jovian, convened a local council in Antioch, at which the Arians signed their agreement with the dogmas affirmed by the Council of Nicaea. But Jovian was soon succeeded by Valens, a zealous supporter of Arianism. Again the heresy temporarily triumphed, again a cruel persecution was raised against the Orthodox bishops, and Meletius was again expelled from Antioch. Emperor Gratian reinstated him, and Meletius resumed his leadership of the church. But the turmoil in the Church of Antioch continued: the supporters of Paulinus did not recognize Meletius.

St. Meletius made every effort to bring about an agreement. He was zealously assisted by St. Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea, who persuaded Christians to stand firm in Orthodoxy. Meletius enlightened his flock with wise teachings and gave everyone an example of a pious Christian life. He was filled with meekness, humility, and fortitude of spirit.

With him, St. Simeon the Pillarman undertook his very difficult feat. Hearing that the ascetic was chained to a huge stone with an iron chain, St. Meletius climbed to the height to him and said to him: "A person can control himself without chains. Not by an iron chain, but by will and reason, he must chain himself." Simeon, realizing the justice of these words, threw off the chain from himself and increasingly strove to curb his will and perfectly subordinate it to the spirit.

Not long before the death of Meletius, Theodosius the Great (379-39) ascended the imperial throne. Even before his election as king, Theodosius once saw in a dream St. Meletius placing a crown and royal purple on him. This prophetic dream came true. Gratian, feeling too weak to repel the constant invasions of the barbarians, chose his brave military leader Theodosius as his co-ruler. And after Gratian's death, Theodosius became emperor and marked his reign with victories and wise regulations, through which he earned the nickname the Great.

The discords and disagreements of that time continued to excite the Church. In addition, another heresy arose - the heresy of Macedonius, who rejected the divinity of the Holy Spirit, which is why the followers of this heresy were called "spiritual fighters" (see also Early Christian heresies, ed.).

Theodosius, wishing to put an end to the disputes, convened a council in Constantinople in 381. This was the Second Ecumenical Council. At it, the heresy of Macedonius was condemned, and the Symbol of Faith was supplemented with the doctrine of the Holy Spirit. Among the other bishops, St. Meletius was summoned to Constantinople, who was to preside over the council. Theodosius, who had not seen him before, recognized in him the same old man whom he had seen in a dream placing a royal crown on him.

Meletius steadfastly defended the true dogmas of the faith. He died in great old age before the end of the council. St. was appointed president of the council. Gregory the Theologian. The body of St. Archbishop Meletius was transferred from Constantinople to Antioch and placed near the relics of the Hieromartyr Babel.