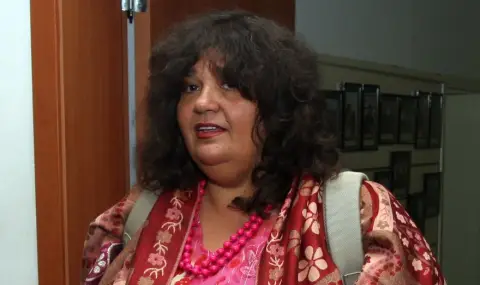

Professor, Doctor of Political Science,

Lecturer of Political Science and Philosophy

at Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski“, Ambassador of Peace and Friendship of the Assembly of the People of Kazakhstan

Tatyana Dronzina

For people like me, who are professionally interested in the development of Kazakhstan, the public appearances and interviews of the president have long been a valuable source of information about the views of some of the political elites on the directions of the country's development. My four-year stay in this beautiful and harsh land with a hospitable and hardworking people, who have gone through various historical trials, helped hundreds of thousands of “disobedient“ to survive the deportation during the Stalinist regime taught me something else - the president is the father of the nation and he should be spoken of accordingly. It's just part of the traditional political culture of the region. Out of good manners. Out of due - and self-evident - respect.

But the latest interview of the President, Mr. Kassam-Jomart Tokayev, made me think that not only the country is entering an irreversible stage of modernization - the political leadership style is also modernizing. Behind the almost ten thousand words of the interview, the image of a new and immeasurably more effective leader, unknown until now in Central Asia, emerged. And not only there.

Instead of a paternalistic, sacralizing or charismatic-populist discourse, Tokayev demonstrates a rational-reflexive, technocratic and even self-critical style, which is more reminiscent of Western European political culture than of the post-Soviet regional canon.

In the Central Asian context, the head of state traditionally presents himself as a “father of the nation“, a bearer of a historical mission and a moral arbiter. In this interview, Tokayev consciously distances himself from such a role. He does not speak of himself as an indispensable leader, but as a responsible administrator of complex, often unpopular decisions, taking political responsibility without heroism. It is significant that the president openly acknowledges structural weaknesses: inflation, the “middle income trap”, dependence on subsidies, distorted social policies, corrupt practices. This violates the unspoken rule of infallibility of the supreme authority, typical of the region.

Tokayev's explicit anti-populism is particularly unconventional. Not only does he not seek instant approval, but he openly states that reformers rarely receive recognition and that "history is more favorable to conquerors and populists". This is a highly atypical statement for a political leader in a region where legitimacy is often maintained through symbolic gestures and social clientelism. In this sense, Tokayev builds an image of an "uncharismatic reformer" who relies not on emotional mobilization, but on rational conviction and long-term vision.

The president's personality is also clearly revealed through his intellectual language. References to the “dictatorship of law“, “social contract“, the cognitive effects of social networks, the culture of reading, the technological watershed of artificial intelligence, and even the moral economy of taxation outline the profile of a president-intellectual, rather than a traditional patron of power. In Central Asian conditions, such a discourse is rather an exception, as it presupposes a society capable of having a complex conversation about public policy, and not just reacting to slogans. And yes, the fact that such a leader is emerging shows that the young consolidating Kazakh nation is already ready to be an equal partner in such a difficult but necessary dialogue.

Another atypical feature is the critical and distant attitude towards the economic elites. Tokayev does not demonize them, but he does not idealize them either. He insists on "creative patriotism", moral responsibility and social solidarity, without hiding the tension between the state and oligarchic structures. This position differs from the classic model of symbiosis between power and business, characteristic of many post-Soviet regimes.

Perhaps the most significant unconventional feature of Tokayev's personality is the rejection of personal mythology. The interview lacks: a cult of personality; historical messianism; appeals to sacred legitimacy. Instead, the president talks about institutions, procedures, laws, programs, indicators and mistakes. This turns his image into a modern "institutional president", rather than a symbolic supreme leader.

The interview clearly shows that Kassam-Jomart Tokayev represents an atypical leadership type for Central Asia: rational, anti-populist, intellectually oriented and institutionally minded. From a political science perspective, the interview does not simply inform about policies, but reveals a transformation of the very model of power in Kazakhstan, in which the personality of the president plays a key - and in this case - unconventional - role. The most successful Asian countries are led by such personalities. I firmly believe that this also applies to Central Asia.