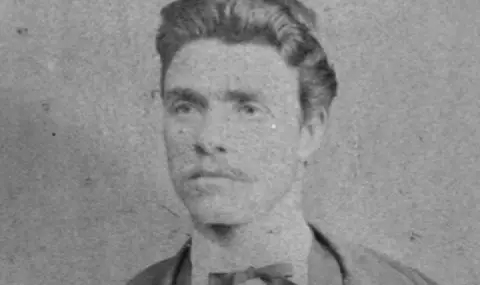

Vasil Ivanov Kunchev was born on July 6 (July 18 new style) 1837 in Karlovo. In 1845, he began his education at the cell school in his hometown, and a year later he was already studying at the local mutual school. Only at the age of 14 he was left without a father and the care of young Vasil was taken over by his uncle Vasiliy Karaivanov.

In the period 1852-1854, he lived in the local Svetogorsk metoch and studied church singing. After his uncle moved to Stara Zagora, Levski followed him and graduated from the second grade of the Stara Zagora grade school. Because of the boy's excellent success, the uncle promises that one day he will send him to study in Russia. That never happens. In 1856-1857, the young man studied at the priestly school of Daskal Atanas Ivanov in Stara Zagora, and in the following year he accepted a monastic deacon named Ignatius. In 1858, he was ordained as a hierodeacon and became a church singer in the Church of the Holy Mother of God. in Karlovo. This reminds the magazine “Bulgarian History“.

In 1861. As a result of the economic crisis in the Ottoman Empire and the economic policy that oppressed the Bulgarians, there was a stir in the revolutionary circles. Stoil Popov from Kalofer and Levski made one of the first efforts to raise the people to struggle. At that time, Bulgarian society was extremely unprepared for a rebellion, which is why the Deacon's first revolutionary attempt was unsuccessful.

Instead of giving up the people's cause, on March 3, 1862, Levski left his hometown and headed for Serbia,

to join the First Bulgarian Legion,

organized by Rakovski. According to legend, during military exercises, he made a “lion leap” and that's how it got its nickname. Here Levski made contacts with the Bulgarian revolutionary intelligentsia and gained his first combat experience, fighting bravely with the Turkish units. After the disbanding of the legion, he joined the troop of grandfather Ilyo voivoda. In 1863 he was briefly in Romania. Summer is back in Bulgaria. He was imprisoned for several months in Plovdiv, because of his participation in the legion, but after the intercession of prominent Bulgarians, he was released. In the winter of the same year 1863, he briefly attended Joakim Gruev's grade school. Curiosity is a main feature of Levski's character, but the disappointment of his uncle's empty promises drives him away from science and towards revolutionary ideas.

From 1864 to the beginning of 1867, Levski worked as a teacher in various Bulgarian villages (Voinyagovo, Enikoi and Kongas). He teaches the children to read and write, tells them stories about Bulgaria's glorious past, sings folk songs to them and often teaches his lessons in nature. Along with his daskal activities, he developed revolutionary propaganda and prepared local squads that resisted Turkish and Circassian bandits. In the spring of 1867, he went to Romania, where on Rakovski's recommendation

was chosen as a byraktar in Panayot Hitov's squad.

In Belgrade, he strengthened his acquaintances from the First Legion and met new revolutionaries, among them Angel Kanchev and Lyuben Karavelov. Soon after the legion was organized, the Serbian government became extremely hostile to the legionnaires, and eventually the Second Legion was disbanded. The behavior of the local authorities changed Levski's revolutionary outlook forever. He realizes that any aid provided by a foreign government is by no means selfless. So far, Apostola has agreed with Rakovski's theory that the rebellion must be achieved through the intervention of troops entering Bulgaria from abroad.

The experience with Panayot Hitov's squad, its failure and his first revolutionary steps as early as 1861 suggested to Levski that the revolutionaries' gaze should be directed to the interior of the country. Only the establishment of a stable committee network within the Ottoman Empire could prepare the people for an uprising. This strategy, although initially difficult to impose by the Apostle, was adopted by every future Bulgarian revolutionary organization – all the way to VMRO. In February-March 1868, the Deacon had to postpone his plans due to a serious operation, from which he had difficulty recovering.

Having recovered his health, Levski left for Romania because of the persecution to which the legionnaires were subjected by the Serbian government. In August 1868, he went to Bucharest and contacted the “Bulgarian Society”, which provided the funds for the Apostle's first tour around Bulgaria. In the autumn of the same year 1868, fate, as if jokingly, brought together the giants of revolutionary thought – Vasil Levski and Hristo Botev. The two live in extremely harsh conditions in an abandoned mill near Bucharest and undoubtedly influence each other. Botev was greatly impressed by the personality of the Apostle.

On December 11, 1868 by steamer from Turnu Magurele

The deacon leaves for Constantinople.

From there he began his first tour in the interior of the country, supported by “Bulgarian Society”. Levski visited Plovdiv, Perushtitsa, Karlovo, Sopot, Kazanlak, Sliven, Tarnovo, Lovech, Pleven and Nikopol. He contacts trusted acquaintances and studies public sentiment and the people's readiness for rebellion. He is encouraged by the initial results achieved and on February 24 he returns to Bucharest.

On May 1, 1869, Apostola undertook his second tour. This time it is supplied with information about internal actors, with a power of attorney and a proclamation issued on behalf of the Provisional Government in the Balkans. Naturally, such does not exist, but Levski rightly considers that it will be easier to win people's hearts if he presents himself on behalf of an authoritative organization. Makes contacts in Romania – such as the one with Danail Popov, who initially recommended him to his brother in Pleven, and later served the Apostle as a liaison with the emigrant circles in Wallachia. Popov's brother introduced Levski to people loyal to the liberation struggle in cities close to Pleven, and thus began the construction of the committee network – first in Pleven, and then in Lovech, Troyan, Karlovo, Kalofer, Kazanlak, Plovdiv, Sopot, Chirpan and other settlements. During the second tour, the Apostle reconsidered his assessment of the readiness of the people for an imminent uprising and concluded that much more thorough preparation was needed.

On August 26, 1869, Levski returned to Bucharest. He has a clear idea of the situation in Bulgaria and the possibility of success of the committee network, therefore he must convince the emigrant revolutionary intelligentsia of the rightness of his ideas. At first he met complete misunderstanding among the revolutionaries, who still harbored hopes that help would come from elsewhere. At the end of 1869, Apostola, together with Lyuben Karavelov, participated in the founding of the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee (BRCC). Although Karavelov adopted some of Levski's ideas, the two leaders of the revolutionary movement differed in their basic views. For Karavelov, the participation of the neighboring Balkan nations in the future revolution is absolutely mandatory, while Levski believes that this would help the rebellion, but the main role should be played by the Bulgarian population.

According to the Apostle, until the Bulgarians are fully ready for an independent uprising, they should not enter into any alliances with neighboring nations and governments (he very well remembers the attitude of the Serbs towards the legionnaires in Belgrade). Levski realizes that any negotiations with the Serbian government are pointless, at least as long as monarchical nationalism and the idea of “Old Serbia”, which includes Bulgarian lands, rule in the neighboring country. However, Levski is a supporter of the idea of common actions of the Balkan peoples and of a Balkan federation. But unlike Rakovski and Karavelov, who agree with the idea of a state uniting all peoples and Balkan lands – exempt and non-exempt,

Levski wants an independent Bulgarian state.

He wants the Bulgarian people to be equal to the rest of the Balkan peoples. Levski's attitude towards the Western Great Powers should also be mentioned here – he realized that Western policy tolerated the Ottoman Empire in view of the colonial interests of the great powers interested in the Eastern Question.

Unlike conservative circles in the national movement, Levski places relations with official Tsarist Russia on a principled basis.

Lewski's desire for the independence of the movement, for its purity, without the interference of foreign agents, regardless of which countries they are from, stems mainly from his national-patriotic considerations. It is for this reason that in 1869, when he encountered a Russian agent recommended by the Odessa Bulgarian Board of Trustees as a good patriot, he quickly expelled him.

Disappointed by the misunderstanding he encountered among the emigrants, Levski returned to Bulgaria in May 1870, began to complete the construction of the committee network and the creation of the VRO (Internal Revolutionary Organization). Lovech was chosen as the capital of the organization, and the committee there is also considered the BRCC. In this way, in the years 1870-1872, there were not only two main ideologies in the Bulgarian revolutionary circles, but also two central committees – The caravel in Bucharest and Levski's, which operates in Bulgaria. VRO is increasingly taking on the appearance of a powerful revolutionary organization.

Apostola sees that funds are needed for the case,

which can be provided by the scumbag class he despises. The collection of money, according to the Deacon, should be voluntary, but in case of refusal, revolutionary pressure is allowed.

Toward the end of 1871, the VRO was the only real force capable of putting the Bulgarian question on the agenda. The committees began active work to attract supporters, to collect funds and purchase weapons. Levski does not completely terminate his ties with the Bucharest BRCC – maintains relations mostly through Danail Popov. In 1871, the Central Committee sent him two assistants – Angel Kanchev and the infamous Dimitar Obshti.

Along with the organizational strengthening and completion of the VRO Levski focused attention on the drafting of a law that would serve as the organization's program and statute. There is no exact information on when this document was produced, but it is assumed that it was completed in August-September 1871. Levski calls it “Order to the workers for the liberation of the Bulgarian people”.

Namely in the “Order” (its first part) Levski presents his views

for the future uprising. In this document, the revolution is seen as a universal people's cause, in which all social strata should be involved: the rich, who have means; the scholars who have knowledge; all who can bear arms. An insurrection is foreseen in the winter, because at that time the men are in the villages and towns, and the Turks will have difficulty in their actions. In the second part of the “Order” The Apostle defines the organizational structures, rights and duties of the committees and members. The Central Committee can make decisions about the outbreak of the uprising, the attraction of allies and armaments. The private committees are the nucleus in which the people's revolution must be realized and brought to a successful end. An interesting fact is that when drafting the statute/programme, Levski gives the committees the opportunity to give ideas, since the political platform of the organization clearly says – all questions must be decided by “supervote”.

From the beginning of 1872, the VRO took a course for unification with the Bucharest BRCC.

Naturally, this activity of Levski was welcomed and from April 29 to May 5, 1872, the first general meeting was held in Bucharest. Domestic workers have priority in the quota over expatriates – 33 at 17. At the first meeting on April 29, a commission was elected, consisting of: L. Karavelov, V. Levski, Kiryak Tsankov and Todor Peev, tasked with drawing up the program and statutes of the Central Bank of Ukraine. The commission finished its work the same day, since apparently the documents were specified in advance in the meetings between Levski and Karavelov. These meetings took place in Karavelov's home in Bucharest, immediately before the opening of the meeting. Levski's project on the structure of the BRCC was ignored at the expense of Karavelov's ideas. Instead of two central committees (in Bucharest and Bulgaria) as before, it is assumed that there will be a single BRCC with an unknown location.

Levski made concessions in the name of unity between the internal organization and the emigrant activists. However, these compromises do not affect the foundations of his revolutionary-democratic platform. His ideas about the great strategic questions of the revolution succeeded in imposing themselves. According to the new program, the main goal of the BRCC is the liberation of Bulgaria through a revolution: “moral and armed”. The deacon was chosen as the “chief apostle” of all of Bulgaria. Also, every member of the Central Committee (CCC), “wherever he may be, can represent the entire Central Committee, if only he has in his hands a “authorized letter”. Such a letter was provided to Levski and he received unlimited (within the organizational statute) powers for his activities inside the country.

With the power of attorney on July 1, 1872, Levski returned to Bulgaria and continued his work on organizing the committees. In the meantime, he turns his attention to supplying weapons. Forcible collection of funds, mostly from hoarders, is becoming a common practice. He makes a request to Karavelov to provide, through the Serbian government, training for 150-200 Bulgarians at the Belgrade Military School, who will later become the military leaders of the rebellion.

After the meeting in Bucharest, the organizations in Bulgaria became more and more, and the people appointed as assistants to the Deacon did not help him much. For this reason, he decided to divide the country into revolutionary districts – Orkhaniski (Botevgradski), Turnovski, Slivenski, Loveski and others. Each district center should lead the local revolutionary committees in the district. A secret police was created for general control of the activities of the committees and for monitoring the enemy. A secret mail is also formed, equipped with passwords, codes and nicknames. The organization of districts throughout the country was thwarted by the upheavals that occurred in the BRCC in 1872 and 1873.

Dimitar Obshti is considered to be the main culprit of what happened.

Commissioned by the Central Committee to be Levski's assistant, Obshti is very undisciplined, self-righteous, petty, talkative and generally unsuitable for revolutionary activity. Among other things, he intrigued against the Apostle, seeking to seize his functions, even succeeding in setting up some private committees against him. Levski even wrote to the Central Committee with a request to “rein in” Dimitar General. The Central Committee issued an opinion confirming Levski's leadership function. He was given the right to give a final warning to the Generals and if further offenses followed, to impose the death penalty, but as events show, this proved fruitless.

The Deacon initially agrees that robbing government institutions should become a fundraising practice, but only when the organization is well established and ready to defend itself against the backlash of the Imperial authorities. That is why he categorically forbids Dimitar Obshti to carry out the planned robbery of the Turkish post office in the Arabakonak pass. Despite the ban, General acted on his own and on September 22, 1872, carried out the attack. Initially, the police accepted the version that what happened was the work of “dismissed soldiers”, as reported by some witnesses. Due to the talkativeness of a few of the participants, however, the authorities soon understood the true purpose of the robbery and caught the organizer, Dimitar Obshti. The arrested, instead of following the unwritten laws, decides that he must show the world that

heist is a political act, starting to reveal names and details

around the organization.

The Turkish government receives indisputable evidence of the existence on the territory of the empire of a conspiratorial rebel organization led by the already wanted Vasil Levski. After learning that Dimitar Obshti is releasing everything, Apostola warns the local organizations to take measures. Meanwhile, the Central Committee comes out with a vague and inadequate position regarding the robbery. He ordered that the prison be first attacked and the prisoners released, and a day later he insisted on a premature end to the uprising. Levski also considered an attack on the prison, but felt that it could have disastrous consequences for the organization. Raising an uprising in an environment of heightened government vigilance is also unthinkable.

However, as a supporter of the principle of the majority vote, Levski does not deny the decisions of the Central Committee alone, but forces each committee to respond to the order of the Central Committee. The general opinion coincides with that of the Apostle – the people are still extremely unprepared for an uprising. The deacon decides that he must immediately go to Romania and dissuade the BRCC about the decision to insurrection by presenting to them the popular sentiment. At the same time, he orders the internal committees to prepare hard for a rebellion anyway. Many comrades advise Levski to hide until the unrest passes. Meanwhile, the government is creating a network of spies to find the Apostle.

Levski left for Lovech, where he arrived on December 25, 1872

The situation he finds there is extremely difficult. The committee does not act adequately, and the police are on their toes. The house of the chairman of the committee, Pope Krastyo, is under surveillance and a meeting between him and the Apostle is impossible. Levski leaves with Nikola Tsvetkov on December 26 for Tarnovo.

In the saddle of Tsvetkov's horse is the archive of the organization. In the evening, they stay overnight at the Kakrina inn, whose owner is also a member of the committee – Hristo Tsonev Latinetsa. According to the generally accepted version, Levski was supposed to meet there with Pope Krastyo, who betrayed him. According to other versions, the blame for the betrayal should not be placed on the priest. The apostle of freedom was captured by the guards who surrounded the inn. The deacon tries to shoot his way through, but is wounded and captured. From Kakrina, he was returned to Lovech, and then taken to Tarnovo and Sofia, where he was tried.

In front of the court, Levski behaves extremely firmly

and does not release any details about the organization, taking full responsibility for the activity on itself. Proudly and combatively defends the cause of the revolution and Bulgaria's right to be free. The judges, among whom is the Bulgarian Ivancho Hadzhipenchovich, try all sorts of tricks to get the Apostle to speak. They ask him confusing and misleading questions, they try to outwit the one who has outwitted them for many years. Failing that, judges take another tactic – a number of his former associates are brought before Levski: Didyo Peev, Hadji Stanyo, Petko Milev, the brothers Hadji Ivanovi, Atanas Hinov and others. They all betray the Apostle, but he does not flinch. On January 8, the court will face Levski Dimitar Obshti, who is guilty of what is happening.

Obschi also betrays the Apostle and tells about his deeds. According to a number of memoirists, participants in the process, Levski got up and spat on the traitor.

The trial against Levski remains shrouded in mystery. Neither the Turkish nor the world press writes about him. The world does not know about the drama in the Sofia inn, where a Bulgarian overcame an entire empire with will and faith in the people's cause.

Sentenced to death and on February 6 (18 new style) 1873, the Apostle of Freedom was hanged at the place where his monument stands today in the capital. His death not only caused shock and sorrow among the revolutionary circles in Bulgaria and Romania, but marked the beginning of a crisis and upheavals from which the revolutionary movement will never fully recover.

Levski left to the generations about 140-150 letters and proclamations, in which he set out his ideas about the equality of people, about human rights and freedoms, the idea of democratic government, of communication between peoples and perfect equality between them, the idea of legality and equality before the law – ideas still relevant today.