On February 19 (February 6, old style) 1873, Vasil Levski was hanged. In his last moments, he confessed to the hierarchal vicar of Sofia, Father Todor Mitov: "Whatever I have done, is for the benefit of the people", asking for forgiveness from the father and from God, and to be mentioned in his prayers as Hierodeacon Ignatius.

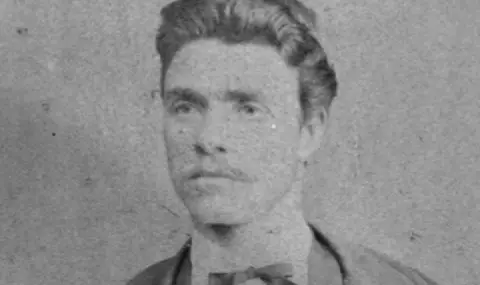

Vasil Levski is the pseudonym by which Vasil Ivanov Kunchev is known – the prominent Bulgarian revolutionary, ideologist and organizer of the Bulgarian national revolution, founder of the Internal Revolutionary Organization (IRO) and the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee (BRCC), Bulgarian national hero.

Levski is also known as the Apostle of Freedom for organizing and developing the strategy for liberating Bulgaria from the Ottoman yoke. Other famous nicknames of his are “The Deacon“ and “Jingibi“ (The Elusive). He traveled the country and created secret regional committees to prepare the national uprising. His dream was a pure and holy republic in which everyone would have equal rights, regardless of their ethnic and religious affiliation.

The Internal Revolutionary Organization created by Levski was the foundation on which the organizers of the April Uprising stood. This uprising and the subsequent Russo-Turkish War led to the restoration of the state of Bulgaria on the European map.

Early years

Vasil Kunchev was born on July 18 (July 6, old style) 1837 in Karlovo to the family of Ivan Kunchev Ivanov and Gina Vasileva Karaivanova. He had two brothers - Hristo and Petar, as well as two sisters - Yana and Mariyka. In 1851, his father died and the three brothers were left to take care of the family of 6. Vasil was already 14 and began to study abazhyluk.

Since 1855, he was a novice with his uncle Vasily, a taxidiot of the Hilendar Monastery in Karlovo and Stara Zagora. In the shadow of his revolutionary activity, three facts remain: First, he received a not bad education for his time, graduating from elementary school in Karlovo and studying for two years in a class school in Stara Zagora, then he completed a one-year course for the preparation of priests at the Plovdiv class diocesan school “ St. St. Cyril and Methodius“. Second, for three years he was a teacher. Third, Levski was fluent in Turkish, Greek and Armenian, which not only proved useful in his revolutionary activity, but also gave an idea of his erudition and intellect.

On December 7, 1858, Vasil accepted monasticism and the name Ignatius in the Sopot monastery “St. Spas“, and in the following year, 1859, the Plovdiv Metropolitan Paisius ordained him hierodeacon in the church “St. Virgin Mary“ in Karlovo.

Revolutionary activity in Serbia and Romania

On March 3, 1862, the hierodeacon left for Serbia and took part in Rakovski's First Bulgarian Legion in Belgrade. Because of his agility and bravery during the battles with the Turks for the Belgrade fortress, Vasil received the name Levski. At this stage, he felt the strong influence of Rakovski and adopted the idea of organizing detachments through which to raise the people in rebellion. After the disbandment of the legion, he joined the detachment of grandfather Ilio Voivode.

In 1863, he left for Romania and after a short stay returned to Bulgaria. In the spring of 1864, on Easter in Sopot, Levski himself cut off his long monastic hair in the presence of his closest friends. From that moment on, he became a lay deacon (servant, assistant) of the freedom of Vasil Levski.

Archimandrite Vasily tried to initiate a church investigation against his nephew, but the Plovdiv Metropolitan threatened Vasily himself with punishment if he persisted in his insistence.

From April 1864 to 1866, Levski was a teacher in the Karlovo village of Voinyagovo, then from March to October 1866 in Enikoi in Dobrudja, and from the end of the year to March 1867 in neighboring Kongaz.

In 1866, on Romanian soil, the Deacon moved in the circles of Hadji Dimitar and Stefan Karadzha. In November 1866, he met Rakovski.

In 1867 At Rakovski's suggestion, he was appointed standard-bearer in Panayot Hitov's detachment. Together with the detachment, he experienced all the difficulties and disappointments during the Balkan campaign in 1867.

Then, together with the detachment, he crossed over to Serbia and joined Rakovski's Second Bulgarian Legion (1867-1868). After its disbandment, he fell ill and stayed for two months in the village of Zajčar.

The enforced idleness gave him the opportunity to rethink the path he had taken. His doubts about the expediency of the Chetnik tactics turned into a conviction that new means must be sought to achieve the ultimate goal. For the first time, he expressed the opinion that preliminary preparation of the people for participation in the liberation cause was necessary. In a letter to Panayot Hitov, he hinted at his conclusions and intentions, informing him that he had decided to do something great for the benefit of the fatherland, “in which if I win, I win for the whole people, if I lose, I lose only myself“.

Levski's distrust of Serbia and the conviction that the Bulgarians should rely primarily on themselves, and not on external forces, grew. The death of Hadji Dimitar and Stefan Karadzha's detachment finally convinced him that preliminary preparation was a necessary condition for the victory of the Bulgarian revolution.

In August 1868, Levski went to Bucharest. His acquaintance with Hristo Botev and their joint life in an abandoned windmill near Bucharest date back to this time.

Organization of revolutionary committees

On December 11, 1868, Levski left for Constantinople by steamer to undertake his first tour of the Bulgarian lands from there for informational purposes, in order to become familiar with the conditions and possibilities for revolutionary activity in the Bulgarian lands.

In early January 1869, he left the Turkish capital and headed for Thrace and Northern Bulgaria. He passed through Plovdiv, Karlovo, Sopot, Kazanlak, Sliven, Veliko Tarnovo, Lovech, Pleven and Nikopol. He talked to his trusted people everywhere in order to win them over to the cause. Hoping that an uprising could be declared in the near future, Levski returned to Romania on February 24.

On May 1, 1869, the Apostle began his second tour of the Bulgarian lands. During it, Levski initiated the construction of the internal revolutionary organization (VRO). The first committee was founded in Pleven. Then he continued the construction of local (private) revolutionary committees in Lovech, Troyan, Karlovo, Kalofer, Kazanlak, Plovdiv, Sopot, Chirpan and others.

Levski's second tour convinced him that the uprising could not be raised as soon as he had thought a few months before. He saw the need for greater preparation of the people, carried out by revolutionary committees, organizationally connected with each other.

After his return to the Romanian capital, Levski sought to convince the emigration that the center of preparation for the upcoming uprising should be transferred to the interior, that the Bulgarians should rely on their own forces, not on external help. The emigrant activists were aware of the need to organize the people, but no one had a plan for who would do it and how. They also had difficulty parting with their traditional concepts of foreign help and leading the revolutionary movement outside the country.

Disappointed by emigration, in May 1870 Levski returned to Bulgaria and began to complete the construction of a committee network. By the end of 1871 he managed to create a dense network of revolutionary committees, united in a complete VRO. Levski was the only one of our great revolutionaries who came to the realization that the chorbadzhii should also be involved in the preparations. Their funds were especially needed for the material security of the upcoming uprising. He envisaged receiving these funds voluntarily, but for those who refused to support the people's cause, he introduced revolutionary terror.

Towards the end of 1871, the committees began active work to attract supporters, collect funds and purchase weapons. When the work increased, the BRCC sent two assistants to Levski - Dimitar Obshti and Angel Kanchev.

Capture and death

On September 22, 1872, Dimitar Obshti organized a robbery of the Turkish post office in Arabakonak. Levski was against it, but was supported only by priest Krastyu Nikiforov. The capture of the participants dealt a heavy blow to the revolutionary organization.

Levski received an order from the Bulgarian Revolutionary Committee and Karavelov to raise an uprising, but he refused to carry it out, deciding to take the archives of the Bulgarian Revolutionary Committee from Lovech and transfer to Romania. He was known for the failure of the robbery in Arabakonak, but he did not know that the Turkish police had his photograph and an accurate description of his distinctive features, as well as information on where he could possibly be found.

According to a prevailing opinion among our historians, Vasil Levski was not betrayed by one person, but was the victim of a long chain of police revelations. On December 27, 1872, he was captured by the Turkish police near the Kakrinsko inn near Lovech.

When he was captured, the archive with committee papers remained unnoticed by the mob. The same archive was preserved and later handed over to Zahari Stoyanov. The missing money was found in 1972 in the foundations of Marin Poplukanov's house. There is an assumption that the reason for Levski's capture was betrayal by a like-minded person. According to other studies, there was no betrayal. It has been proven that Father Krastyu did not have accurate information about Levski's plans.

Until the very end, the Ottomans did not know who they had captured and Levski was taken to Tarnovo to be identified. Only there did it become clear who he was. Only a few guards went to Kakrina, and if they knew who they were capturing, such a small number would not be logical.

Levski, who was guarded by only 20 guards during his journey from Tarnovo to Sofia, hoped in vain until the last that he would be released by like-minded people. There he was brought to trial. The apostle built his defense on the foundations of the rights of Christians according to Hatihumayun, so as not to betray anyone and the organization. He emphasized several times that he was looking for legal ways to change life in the Empire. Levski distanced himself from the activities of Dimitar Obshti in order to avoid criminal charges.

The Grand Viziership was expected to release everyone except the mail thieves, because a political trial was not in the interest of Turkey and damaged its authority in Europe. The instructions to the judges stated that only the leaders should be severely punished.

The trial commission was composed of Ali Said Pasha, Shakir Bey and Ivancho Hadzhipenchovich. The court also included Bulgarians: h. Mano Stoyanov and Pesho Todorov as representatives of the Bulgarian municipality in the city. Muslims and Jews were also included.

The death sentence was issued on 14 and confirmed on 21 January 1873. The trial ended with the commission seizing the functions of a court, which was inadmissible under the laws of the empire itself. Dimitar Obshti and Vasil Levski were sentenced to death by hanging, and 60 defendants were sentenced to imprisonment and exile. The sentences were confirmed by the Sultan as appropriate. In order not to harm Turkish diplomacy, no large-scale investigations and persecutions were carried out.

The priest, Father Hristo Stoilov, tells about the last moments of the apostle: "The deacon behaved heroically. He said that he was indeed the first, but that there were thousands after him. The executioner put the rope on him and kicked the stool. I burst into tears and turned to "St. Sophia" so that the Turks would not see that I was crying, and I left."

Mikhail K. Bubotinov also gives a description: "On 1873, February 5, Tuesday, a market day in Sofia - 2 hours before dawn, in the courtyard of the pasha's residence - on the site of today's princely palace, an unusual commotion occurred at the pasha's sejmen. By order of Mazhar Pasha, then the Sredets governor, a mule-sergeant was sent to call the butler priest Todor Mitov to get ready... Butler priest Todor got ready in half an hour... And here the governor set off in a carriage with his retinue, consisting of about ten people. Immediately after them, Vasil Levski, who had just been taken out of prison, was brought to the middle of the square, escorted by a platoon of guards and 4 platoons of soldiers, dressed in his suit, as he had been caught by the authorities at the inn, with heavy shackles on his legs, but without a court ilyam on his chest. Mazhar Pasha, turning to the priest, ordered him to approach Levski and freely perform his religious duties. As soon as the priest approached Levski, the pasha retreated 7-8 steps and at the same time gave a signal for the people from his retinue to do the same. ...

What Levski confessed about himself in this case could not be conveyed by the priest-confessor. However, in general terms: Father Todor told me that Levski stood alert and in the presence of spirit said: "In my youth I was a hierodeacon Ignatius, I left the service in the consciousness that I was called to perform another, more urgent, higher and more sacred service to the enslaved fatherland, which ... hopefully!" Here Levski burst into tears and asked the priest to pray to God for Hierodeacon Ignatius ... "

THE HANGING OF VASIL LEVSKI

Oh, my mother, dear homeland,

why are you crying so pitifully, so sweetly?

Raven, and you, damned bird,

on whose grave are you croaking so hideously there?

Oh, I know, I know, you are crying, mother,

because you are a black slave,

because your sacred voice, mother,

is a voice without help, a voice in desert.

Cry! There, near the city of Sofia, I saw a black gallows, and one of your sons, Bulgaria, hung on it with terrible force. The raven cawed hideously, ominously. Dogs and wolves howled in the fields. Old men prayed fervently to God. Women wept, children screamed. Winter sang its evil song. Whirlwinds chased thorns across the fields. Cold, frost, and hopeless weeping brought sorrow to your heart.

"The Hanging of Vasil Levski" is Botev's last song. It was probably composed towards the end of 1875, because it is not included in "Songs and Poems". It was printed in "Calendar for 1876" under the image of Vasil Levski.

Despite the fact that Levski was hanged on February 18, it is customary to celebrate this date in Bulgaria on the following day, February 19.

In 2007, a national poll by BNT named Vasil Levski as the greatest Bulgarian of all time.